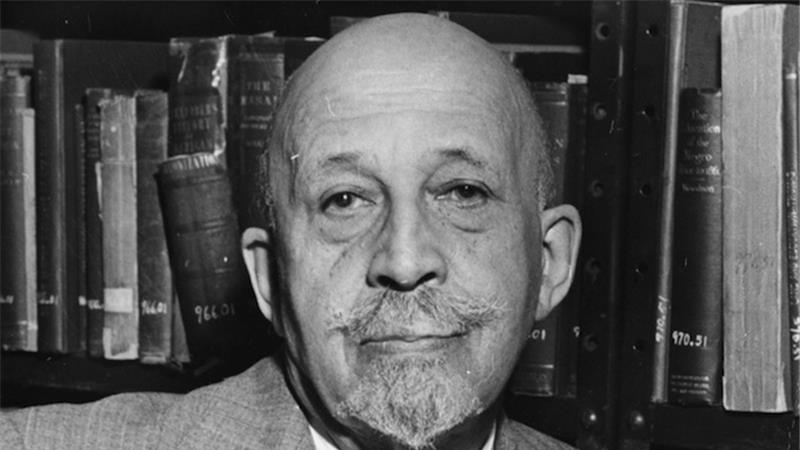

In his book The Souls of Black Folk, a powerful analysis of racism’s effects on African Americans and a critique of US society, W E B Du Bois theorised on the concept of “double consciousness”: the self-measuring and regulating mechanism that causes African Americans to “look at one’s self through the eyes of others”, denying them the ability “to attain self-conscious manhood” and “merge his double self into a better and truer self”.

He explained further: “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness: an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two un-reconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

It is important for me to bring Du Bois’ concept of double consciousness into the discussion of Muslims, the colonial and the post-colonial, because of my personal interest as a Palestinian in his work and in all issues related to race and racism; and because of my conviction that “double consciousness” is a condition that afflicts all who inhabit the modern Eurocentric world.

Indeed, how we define ourselves; the superior or inferior, who we seek to emulate, the Fair and Lovely we purchase to whiten our bodies, the history, novels, movies and media we devour, the political structures we build, the cities we desire to visit, the music, fashion, the things we hold important, the food and corporate symbols we all share, etc., are all burdened by double consciousness.

Eurocentric world

The “known” world is Eurocentric and produces double consciousness in all subject people it came in contact with in the past and present. The world today is Eurocentric: The history, economy, politics and media are Eurocentric; the Muslims inhabiting the modern world are Eurocentric; the definition of the human and “consciousness” itself in today’s world is Eurocentric. Thus Muslim, as a category, is a by-product of a Eurocentric enterprise whereby the focal point is demonstrating one’s Muslim-ness to an external that is constantly negating its value.

Muslim’s double consciousness was formed in the colonial period and continues in the post-colonial state. When the terms Islam and Muslim are used, they have to be understood within the confines of colonial epistemology, for the pre-colonial conception of both is no longer present, and whatever vestiges are located or discovered, are experienced through the colonial cartography. What colonisation has done was to construct an external objectified Islam and Muslim, an ideal inferior and a static pre-modern Other through which the Eurocentric colonial “modernisation” project can be rationalised in the Muslim world.

The Muslim subject in colonial discourse is ahistorical, static and rationally incapacitated so as to legitimise intervention and disruption of the supposed “normal” and persistent “backwardness”. Indeed, the colonial expansion was theorised prior to contact with the Muslim subject through a set of rationalisations to satisfy foremost the colonial citizenry that the theft, pillaging and destruction is for a higher purpose, i.e. civilisation itself. The Muslim’s subjectivity emerges out of this colonial rationalisation and is brought into the modern as the constantly un-modern and persistently resistant to civilisation, therefore necessitating constant intervention.

External identity marker

As the colonial project took hold, a major epistemological order was set in motion and Muslim-ness emerged as an identity marker that essentially acted out the meaning of being Muslim in colonial terms. Islam was reduced from a comprehensive and intact world view to an external identity marker in reaction to, and in defence of, what was thought to be core constitutive elements revolving around religious observances, formulaic structures and a force to maintain order. While each of these, in a comprehensive system, has its place, in colonial structures, they were intended to keep the pre-modern in a pre-modern-induced static state and push it out of contesting the hegemonic modern colonial project and its imposed world view.

Muslims began to see themselves through the constructed colonial lens and thus Islam went from being a unified system of meaning, into an objectified external construct, seeking meaning in an imitative project of a perceived coloniser’s success. His success was measured by science and technology, as well as a particular mode of religious discourse revolving around acting religious in more or less material ways. What Muslims were urged to reconstruct was the Europeans’ experience with religion as the only valid way to enter into the modern world.

The outcome was spiritual materiality that was intended to illustrate Muslim-ness in the face of negations and the complete absence of indigenously adhered to system of meanings. In this imitative transformation, one can see the emergence of the distinct difference between being spiritual versus acting spiritual, whereby the focus is on the act as an external objectified manifestation of wanting to be seen commissioning a religious act by the external colonial superior. Demonstrating Islam to an external is different than living Islam with all the ups and downs of “normal” life. In acting Muslim, a person is preoccupied with answering and resolving the racialisation and otherisation central to Eurocentric discourses and coloniality. One can never resolve or answer these questions for it is impossible to respond to a negation rooted in a racial matrix, historically set and connected to global Eurocentric knowledge production.

At odds with true self

The colonised Muslim has been through a total mental, physical, political, economic, cultural, educational and social domination program that has produced a shadow figure and a constructed identity desiring to be a complete and wholesome self once again, while on the other hand trying to demonstrate the ability to be a modern subject for the coloniser’s satisfaction.

The double consciousness effectively creates a Muslim identity that is constantly at odds with the “true” self that has to be suppressed because the world it belonged to no longer exists, and only traces of negations are allowed to persist. In this sense, the identities of the colonised Muslims are constructed similar to other colonised subjects as a series of negations, inadequacies and incapacities. The imprint on the mind and the double consciousness of the Muslim thus revolves around two separate and conflicting sides that can’t be reconciled and are at odds, for each reminds the other of that which he/she is not and what can’t be attained.

“[H]ow little we know about their daily longings, their homely joys and sorrows, of their real shortcomings and the meaning of their crimes,” wrote Du Bois about African Americans – a remark which is quite valid about Muslim men and women today.

Indeed, this is the case with the volumes of “studies”, daily briefings, and polling data which are supposed to answer “our” questions but never really dare to find out Muslim questions or hear their diverse responses. The studies, books, research, conferences, surveys and observations of the colonial Muslim subject have not produced, nor will begin to produce, the answers to the multitude of problems found among the “natives”, for all of them are aimed at answering and solving imperial problems. From writings compiled prior to the arrival of Napoléon to Egypt to the current research across the Arab and Muslim world the main preoccupation is with imperial questions and problems. The process goes ever deeper to the notion of educating the Muslim subject and building initiatives and resources directed at producing the new, more docile, and less resisting strain of Muslims.

Challenging colonial subjectivity

The more difficult Muslim strain is the one that asserts political agency, for it challenges colonial subjectivity and the requirements for the pre-modern not to have attained political consciousness since that is a phenomena known only to, and developed by, the Eurocentric world. Muslim political agency is suspected, fought and neutralised, for if allowed to develop on its own, it would bring into focus a historical continuity, indigenous knowledge and resourcefulness that may possibly lead to the disruption of the colonial paradigm and breaking the hold of double consciousness.

The African American response to the racial predicament, in Du Bois’ view, was seen articulated in three distinct ways: “a feeling of revolt and revenge; an attempt to adjust all thought and action to the will of the greater group or, finally, a determined effort at self-realisation and self-development.”

In Muslims response to colonisation, “adjusting thought and action to the will” of the coloniser continues, despite the end of direct control; we are yet to shift into “self-realisation and self-development”. Feeling the urge to extract revenge will not lead to uplifting the Muslim world or altering the conditions present today, but will possibly only prolong the suffering and the intervention. The more difficult, and in the long run more transformative, choice is the one centred on an education and a religion that liberate the self and society; offer a sustainable and distributive economic model; and espouse an inclusive and human-centric political structure and cultural production, celebrating and honouring the diversity of humanity. This is Islam’s higher calling.