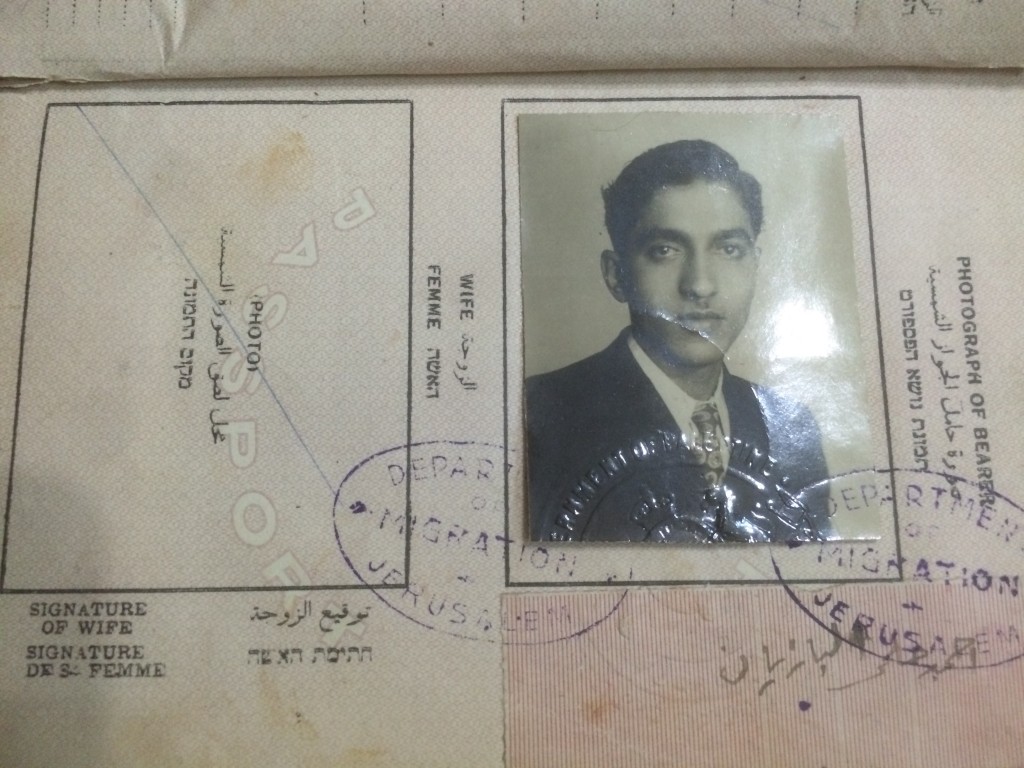

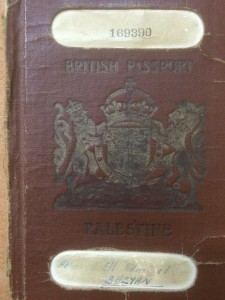

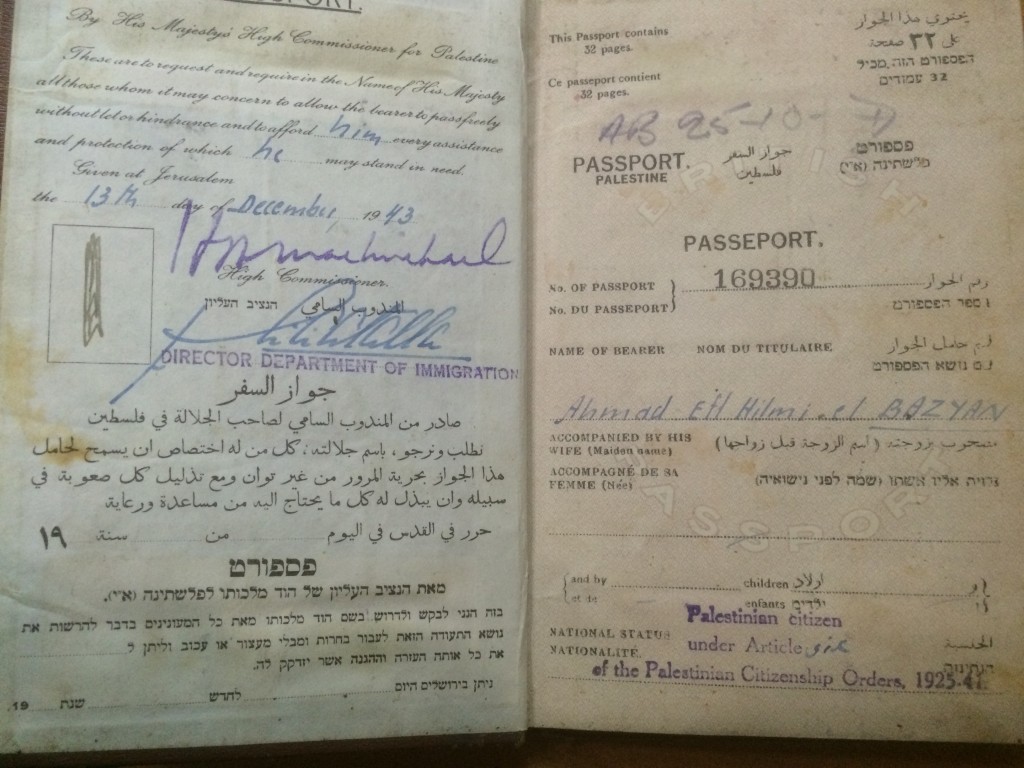

While visiting my mother, who was recuperating from a major operation in Jordan this past December, I took the time to go through family photos and documents. Aside form the usual collections of early childhood photos and funny faces at events, my late father’s Palestinian passport from the British mandate period captured my attention. It was still in excellent condition and full of stamps and travel details. I had seen, held, and examined it while growing up; however, this time I approached it as a historian who writes on colonialism and Palestine. His passport is both an important family possession and a piece of history that verifies Palestine’s presence on the map before Zionism began to erase it. Issued in 1943, it is a British passport bearing the number 169390, which is designated for the Mandate of Palestine.

The passport, maps, currencies and all colonial documents use “Palestine,” including, interestingly enough, the British-Zionist discussions before, during and after WWI. Likewise, the name Palestine (hereinafter “Palestine”) was used during the late Ottoman period. The area’s indigenous population used the land’s major cities and towns as points of reference to its identity; however, this does not mean that they somehow failed to identify with and conceptualize Palestine as their cohesive homeland.

Zionist settler colonialism continues to ask Palestinians, erroneously, to present their nationalist credentials to validate their asserted right to the land. But nationalism, which is a modern phenomenon, cannot be used as the measuring stick to ascertain the indigenous people’s right to the land, for this right predates European nationalist concepts. The aim is not to establish rights or claims, since the name of a land or a region shifts even among its indigenous populations. Moreover, the presence or the lack of a name neither changes nor removes the indigenous Palestinians’ right to their own land.

What’s in a name? The answers to this very profound question are connected to every aspect of the human experience, including our own individual names and identity. A name enables us to construct a mental map by which we can shape our understanding of objects, things, and concepts in the world. At a higher level, it allows us to formulate abstract and complex ideas that we can use to innovate and reach new horizons. If a name can help us unlock human potential and shape the mental map that makes it possible for us to relate to the physical world and abstract thinking, then the critical question is what happens when that particular name faces structural erasure and political obliteration? Why was this specific goal such an important part of every colonial project? Is it coincidental, or does it point to something deeper at work?

What’s in a name? The answers to this very profound question are connected to every aspect of the human experience, including our own individual names and identity. A name enables us to construct a mental map by which we can shape our understanding of objects, things, and concepts in the world. At a higher level, it allows us to formulate abstract and complex ideas that we can use to innovate and reach new horizons. If a name can help us unlock human potential and shape the mental map that makes it possible for us to relate to the physical world and abstract thinking, then the critical question is what happens when that particular name faces structural erasure and political obliteration? Why was this specific goal such an important part of every colonial project? Is it coincidental, or does it point to something deeper at work?

Palestine. The asking of what’s in a name. Clever people will immediately want to focus on the name’s etymology and trace its origins, as if this will somehow answer the question of how “Palestine” threatens Zionism as well as its adherents and supporters. Certainly, one aspect of this name revolves around a mistaken or imperfection in the word’s etymology or origins. Those who are determined to negate its validity on the basis of etymology claim that the word’s imperfect etymology removes the Palestinians’ rights to their land. The absurdity of this proposition should be obvious to all; however, such clarity has never stopped people from making legitimate fools out of themselves in public. It seems that this has become a valuable skill in the current Israeli Knesset.

Another approach can be traced to those who consider themselves true history buffs and more sophisticated: The Romans were the ones who coined the name “Palestine.” But how does their decision to call it “Palestine” or “a piece of land down below” answer “What’s in a name?” andwhy so much human effort and financial capital are being spent to erase this word from public discourses? In short, their argument is that Palestinians had no political structure or understanding of themselves as a people until the Romans “formed” this name to disassociate the land from its “rightful” owners: the ancient Israelites.

Of course, there is no need to remind them that they themselves changed the land’s original name – the Land of Canaan – when they invaded it under Joshua, according to the Old Testament that they cite as evidence. In other words, they seek to prove their claim by citing a text that actually disproves their fundamental claim.

Yet other people will point to the Muslim Arabs who arrived in the mid-seventh century and, after a while, began referring to the region as “Palestine.” Not to leave things simple and intellectually unpolluted, this group likes to speak of an Arab invasion, forced conversion and a host of other Orientalist toolkit arguments to substantiate the non-existence of “Palestine.” The invasion argument implies that Arabs were interlopers who suddenly arrived in the form of a small army and managed to transform the demographic landscape for the foreseeable future. This is a simplistic argument at best, and yet it continues to get considerable mileage and appears even in supposedly scholarly texts.

This particular claim seeks to disassociate Palestine from its Arab heritage and, at the same time, pushes a classical form of Islamophobia that posits Islam’s violent nature and supposedly forced conversion policies. If the long-ago Arabs “invaded” Palestine, then the current Palestinians, being part of the current Arab world, have no right to this land. Moreover, the Zionists are only reclaiming their “own ancient homeland.” But there is a problem here: History does not substantiate this asserted linkage of an Arab military invasion with religious conversion or that the region’s conversion was slow and forced. At the beginning of the 7th century, Palestine’s population was Arab and the Arabic-speaking tribes inhabiting the Jordan Valley, Al-Khalil and around Jerusalem had been trading with Arabian tribes, even those that lived in Mecca, before the appearance of Islam.

In addition, the Zionist attempt to remove all references to Arabic-speaking Arab Christians who have always lived in the region, and to maintain a singular focus on Islam and Muslims, is deliberately designed to play into existing Orientalist tropes. The narrative of Palestinian Christians is problematized by concentrating only on those periods of contestation between Arab Muslims and Arab Christians, while inserting as often as possible the West and Zionism as supposed defenders of Eastern Christians. Yes, the Arab world’s Muslims and Christians have their conflicts, contradictions, and periods of utter hostility, for such is the nature of human experience. But Western and Zionist “civilizational” colonial and post-colonial missions have hardly solved or ended such realities.

Recent history shows that Zionism is still making a concerted global effort to erase “Palestine” from books, maps, official documents, tourist information and films. Some efforts have reached such extreme levels of censorship and contesting its mere mention in any context that one wonders that if saying “Palestine” out loud would end time itself. The Zionist dream is to root out the very word “Palestine” in order to disassociate it from the land and the people who relate to it as part of their ancient and continued identity formation.

Their very normative colonial discourse seeks to remove the indigenous people’s association with their colonized land so that, at some point in the future, their actual title to the land can be transferred to the colonially implanted citizenry, as happened in the Americas. Here again, a religious text and the colonizers’ God were dragged into the mix to justify the unfolding humanly constructed dispossession and transformation. If the colonizers can maintain the land’s new name for generations, then there is “hope” that one day its future inhabitants will only be able to recall and affirm the colonial name.

But the Zionists are after something deeper: erasing Palestine’s name in order to erase the land’s inhabitants. And yet the more they pursue this goal, the stronger the Palestinians’ attachment to “Palestine” becomes. The organic relationship between the name and the people can only be broken by totally eliminating the latter to make everyone forget the former.

The mere fact that a people refers to it land by name “X” and holds it to be the depository of their historical, cultural, ethnic, religious and social values is sufficient as a point of departure. A settler colonial community that contests an indigenous population’s point of reference to its ancestral homeland can have no standing, regardless of how much paper and ink it wastes to justify itself.

I entered into this “Palestine” discourse because the front cover of my father’s British passport bears this name. The passport, like everything else in Palestine, is contested by settler colonialism and negated on the basis that it is a British invention and undertaken, according to hardcore Zionists, to appease the Arabs at the expense of the Jews. The British, being themselves a most conniving colonial power, acted in their best interests before, during and after WWI. In this case, it meant incubating Zionism to protect their Egyptian colony and secure more territory from the collapsing Ottoman Empire. Moreover, and importantly, the British upper crust and racist elites didn’t like Jews and sending them to Palestine was one way to solve the “Jewish question.” As is often the case, the British said whatever was necessary to secure more power, territory, interest and resources for the Crown. One should never forget their heavy involvement drug dealing in Asia, most notably during the Opium Wars (1839-42 and 1856-60) in China.

Accusing the British of appeasement is certainly entertaining and qualifies for a Comedy Central special or a Saturday Night Live skit, rather than as a legitimate response to using “Palestine” during the Mandate period. The British colonial legacy and machination leave much to be desired when it comes to using such terms as truth, honesty, justice and fairness. It is preposterous to accuse the British of being honest in their colonial policies, as the Irish people’s 800 years of experience with them shows. But the Zionists take their own claim quite seriously.

The existence of my father’s passport is significant on one level but completely irrelevant on another level. Palestine exists regardless of this British passport or any other colonially produced document. The British did not invent “Palestine” to inscribe it on the passport, for Palestine and its people existed before the British arrived, remained after their departure, and are permanently affixed to the land despite their current dispossession.

Once after I had given a long lecture on Palestine’s history, a very angry man insisted that there is no such thing called “Palestine,” to which I replied by thanking him for affirming the name in his effort to negate it. The more the Zionists attempt to contest and negate the existence of “Palestine,” the firmer it is established in people’s mind and in the collective imaginary of the Palestinians.