Imperial Britain Gave Palestine to the Zionists When It Was Still Part of the Ottoman Empire.

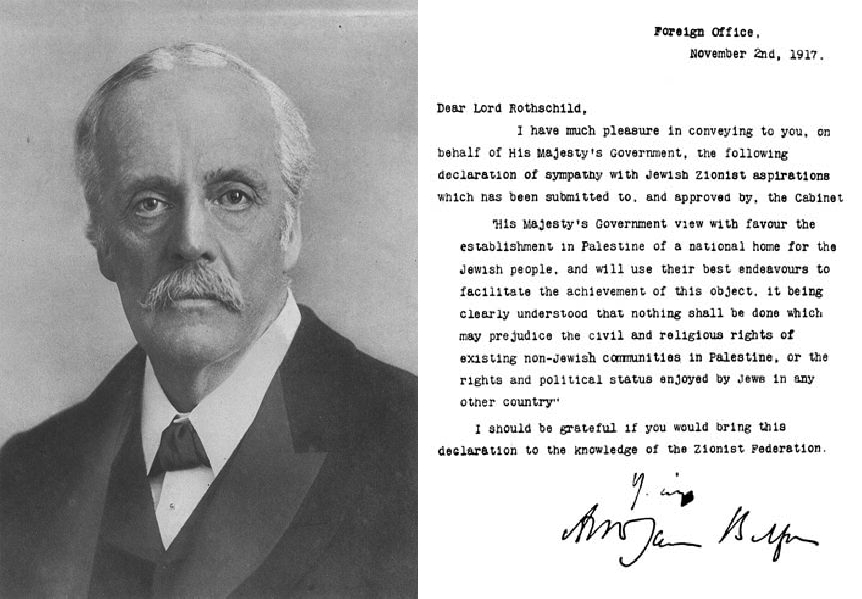

On Nov. 2, 2017, Palestinians mark the hundred-year anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, a letter from British foreign secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour to Lord Walter Rothschild that committed Britain to the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. In 67 words, Balfour and London dispossessed the Palestinians and incubated Zionism, imperial Europe’s last settler colonial project. Certainly, the ongoing conflict in that tormented land is not isolated from the broader colonial legacies in the Global South, and its effects continue to be witnessed to this day.

British colonial policies and political machinations across the globe were designed to aggravate ethnic, religious, economic, and political conflicts in order to keep imperial interests intact by other means. Divide and rule was the strategy of choice. The Balfour Declaration and the adoption of Zionism by the British ruling class was carried out with an eye toward a broader regional divide-and-rule strategy as well as a global plan centered on protecting its colonial possessions of Egypt and India.

As we commemorate this anniversary, it is important to revisit the development of this declaration, as well as the strategy behind it and how it has affected the Palestinians. More importantly, the British government owes the Palestinian people an apology, restitution and a verifiable end to all forms of support that enables Israel and Zionism to continue their ethnic cleansing and dispossession of the Palestinians.

The Balfour Declaration reads: “His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

In succinct terms, the Declaration is a colonial legalism that reeks of dishonesty in each word used and at its very foundation, for its sole purpose is to provide a cover for the outright “civilized” thievery of Palestine. Why does this colonial legalism attempt to masquerade as a type of civilized international law? First, the Declaration was issued on Nov. 2, 1917, at a date and a time when the British had not become the occupying power — the Ottoman Empire surrendered Jerusalem on Dec. 9, 1917. In other words, the British promised a territory over which they had neither sovereign power nor control to a third party.

Second, the Declaration is contained in a letter to a private citizen, Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, lacked any national or international legal standing to claim Palestine as a national home. This British promise concerning a land and country that was inhabited and belonged to its own people, namely, the Palestinians, represents the highest form of illegality.

Third, the letter was intended to be transmitted to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland, which likewise lacked the legal standing to receive and represent claims over Palestine.

Clearly, Balfour communicated and granted to British subjects a territory to which, at that time, Britain had no legal rights. Also, the Zionist Federation did not represent a legal body that could speak on behalf of all Jews inside and outside of Palestine on this subject.

Fourth, the indigenous Palestinians, who made up 97% of historical Palestine’s population, was not consulted or even considered. Fifth, the local Palestinian Jewish population was not consulted about the Zionist settler colonial project, which they forcefully rejected on several occasions when Theodor Herzl sought their support.

Sixth, the Declaration’s actual text is problematic on several fronts. For example, it contains no precise meaning for “a national home,” which is not the same thing as the already established concept of a nation-state. More critically, it introduces the concept of “the Jewish people,” a singular national identity that was, at the time, opposed by most of Jewish populations living as citizens in various Arab and European countries as well as in the U.S. Precisely on this point, the Declaration stated at the end that “the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country” — a way to create a “peoplehood” out of a diverse religious community in order to usher in the Zionist settler colonial project.

Seventh, the Declaration completely erased the Palestinians, for being “non-Jewish” was the only defined characteristic included in the text. Affirming the non-Jewish communities’ “civil and religious rights” is a mockery masquerading as a form of legal protection to a soon-to-be dispossessed indigenous population. The Palestinians, despite constituting 97% of historical Palestine’s population, are only defined as being “non-Jewish.” There is no reference to political rights. On the other hand, the Declaration granted “a national home” to the Zionists and called for the protection of “the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

Here, the inclusion of “civil and religious rights” for the non-Jewish population translates into a British government intent on denying political and national rights to the indigenous Palestinians. The Declaration begins the long and torturous process for them to affirm and establish their national and political rights in the face of Zionist settler colonialism, which was aided and abetted by Britain’s imperial power. Why did the British issue the Declaration and what were the political forces that brought it into existence are important questions.

Certainly, the Declaration fits into British colonial plans that started much earlier than 1917 and involved colonial expansion into Ottoman territories. The fomenting of the June 5, 1916, Arab Revolt and the Sykes-Picot Agreement are two pieces that fitted perfectly into London’s colonial plans. At present, it is taken for granted that the Arab world’s current borders were drawn by British and French colonial administrators and not the region’s various peoples. What passport an Arab carries, the type of citizenship and the name of the state he/she belong to in the Global South is shaped in large part by the former British, French, Dutch and other colonial powers. Consequently, this colonial-era Declaration was specifically issued to dispossess the majority population and replace it with a client European Zionist settler state.

The records show that as early as December 1914, Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith and his cabinet had lengthy discussions on Palestine’s fate — discussions in which the British Zionist leader Herbert Samuel, who held a seat due to being president of the Local Government Board, participated and provided input. Samuel’s memoirs state that he articulated a position on behalf of the Zionists: “I mentioned that two things would be essential—that the state should be neutralized, since it could not be large enough to defend itself, and that the free access of Christian pilgrims should be guaranteed… I also said it would be a great advantage if the remainder of Syria were annexed by France, as it would be far better for the state to have a European power as neighbor than the Turk.” The Cabinet’s agenda on the issue was influenced to a large extent by Samuel’s memorandum, “The Future of Palestine,” which centered on promoting Zionist plans for a new country.

The Declaration did not come out of a vacuum. Rather, it was the result of deliberate and careful considerations and the involvement of Zionist leaders in Britain and the U.S. with a group led by Supreme Court Justice Brandeis. This group offered to help with the drafting and lobbying efforts directed at President Wilson and the State Department. The final version was agreed upon after at least four known drafts and language changes sent back and forth between U.S. and European Zionist leaders and political operatives. The short text, a mere 67 words, “was weighed to the last penny-weight before it was issued.”

Chaim Weizmann, the Zionist leader, held that it was critical to get Wilson’s support. This support arrived in the form of a note sent on Oct. 13, 1917, and was due to the intense work of Brandeis and his dedicated Zionist group. In his “Zionism” (1926), Leonard Stein notes that the Declaration “was by no means a causal gesture. It was issued after prolonged deliberations as a considered statement of policy.”

In his “History of the Peace Conference in Paris” (1920), H.W.V. Temperly (ed.) states, “Before the British Government gave the Declaration to the World, it had been closely examined in all its bearings and implications, and subjected to repeated change and amendment.” In his two-volume “History of Zionism: 1600-1918” (1919), Nahum Sokolov, who served as president of the World Zionist Federation from 1931-35, writes that “every idea born in London was tested by the Zionist Organization in America, and every suggestion in America received the most careful attention in London.” Lastly, “The Balfour Declaration was in process of making for nearly two years,” writes Stephen Wise, chairman of the Provisional Zionist Committee in New York, while adding that “its authorship was not solitary but collective.”

Many reasons are given for the British issuing the Balfour Declaration. Some are connected to immediate strategic concerns, whereas others focus on long-term planning for the region. Not all British Jews agreed with the Zionists’ plan, and thus two camps gradually emerged. The Zionists saw that this split could damage the efforts underway to secure Wilson’s and American support for their project. Leading the counter-Zionist effort in London was the Jewish assimilationist camp led by Edwin S. Montagu. For Montagu and others, the Declaration threatened the status of Jewish communities in Europe and the U.S. with the possibility of raising the issue of dual allegiance, a subject of intense debate and draft changes that brought about the phrase “the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.” Furthermore, Montagu took offense at the Declaration and charged London with forcing him and other British Jews into a new ghetto.

As far as the reasons behind issuing the Declaration are concerned, the then-Prime Minister Lloyd George, whose legal firm Lloyd George, Roberts and Co. had represented Zionist interests in terms of securing Uganda as a possible homeland, testified before the Royal Commission in 1937 that “stimulating the war effort of American Jews was one of the major motives” for issuing it. In addition, it was also issued to counter the changes brought about by the Czar’s overthrow and the decreased “bitterness of the Jews in Russia,” who were increasingly turning toward supporting more revolutionary movements and less inclined to continue to support the war effort. More importantly Prime Minister Lloyd thought of constituting a “Jewish ‘garrison colony’ in Palestine as a buffer for Egypt and the Suez Canal.”

Critically, the British had interests and needs in the region. Among these were (1) securing the status quo in Egypt (occupied and administered since 1882); (2) creating a buffer protection for the Suez Canal, a vital strategic asset that provided both access to and control of the region’s newly discovered oil fields; (3) retaining its commercial and military advantages, as well as (4) maintaining broader links with its other colonial possessions in Asia and Africa. Furthermore, the incubation of a client Zionist colony would counter the threat of major powers having similar designs or contesting British supremacy in that part of the world.

The Zionists and Weizmann did not shy away from making explicit offers to connect themselves to British interests and proclaim that a Jewish Palestine was “an essential link in the chain of the British empire.” Britain, the Zionists asserted, needed “somewhere in the countries abutting on to the Suez Canal, a base on which, in case of trouble, she can rely to keep clear the road to Imperial communication.” Here is the idea of the Zionist state function of securing for Britain the “vital Cape-to-Cairo and Cairo-to-India routes.”

Even at this early stage, the discovery of oil played an important role in British designs, as can be seen in the idea of an Iraq-Haifa pipeline passing through trans-Jordan, which was already on the drawing board. Interestingly, this idea was revived during and in the aftermath of the 2003 American invasion of Iraq, as well as the additional and new imperial design of a water supply channel to satiate Zionist settler demand in Occupied Palestine. Indeed, to a large extent the British viewed a Zionist state in Palestine as constituting a buffer state that would protect imperial interests in the region with emphasis on Egypt, a critical gate to the empire’s vast trade network and territories. In comparison to India, which was thought to have a set of natural buffer zones in the north, Egypt, with its strategic position, lacks such protection and, as such, a buffer state allied to or incubated by Britain would provide better strategic protection.

The Balfour Declaration must be situated both within the broader British imperial designs intended to create buffer zones to protect its interests and the Zionist leadership’s machinations to secure a foothold in Palestine. As such, Zionism and the Zionist project were born in the imperial womb and functioned within its epistemic foundations. According to the German-American political theorist Hannah Arendt (1906-75), when it came to London’s colonial alliance and machinations, Zionism “sold out at the first moment to the powers-that-be.”

The British promise to the Zionists must be examined within the broader strategy laid out by Herzl some years earlier. Essentially, the Declaration itself, while approved by London, was to all intents and purposes a Zionist authored document that involved more than Englishmen before the Cabinet adopted it and made it the effective policy of successive governments. Being a Zionist authored and debated document, a critical question arises as to its significance for the Zionist settler colonial project. Answering this question takes us back to August 29-31, 1897, and in particular Herzl’s declared intent for his movement: “to obtain for the Jewish people publically recognized, legally secure homeland in Palestine.” The Declaration was the first public document sanctioned by the major Western powers and established the needed framework for securing an internationally sanctioned foothold in Palestine.

Even before the Document’s issuing, Weizman was already announcing on May 20, 1917, that “while the creation of a Jewish commonwealth is our final ideal… the way to achieve it lies through a series of intermediary stages… Under the wing of this Power (Great Britain), Jews will be able to develop and to set up the administrative machinery which, while not interfering with the legitimate interests of the non-Jewish population, will enable us to carry out the Zionist scheme.” The Declaration is part of a staged approach to setting up a state under a major Western power’s protection in order to facilitate immigration and build an institutional framework for its future emergence. While its text is rather short, its implications and inclusion in all subsequent legal documents pertaining to Palestine made it a trans-historical knife directed at the heart of the Palestinians’ right to self-determination.

In conclusion, the Declaration created “legal colonial facts” on paper that were then mobilized to create settler colonial facts on the ground by encouraging and facilitating Zionist immigration, building settlements and systematically dispossessing the Palestinians. In the years following WWI, representatives of the World Zionist Organization were included and actually became parties to the negotiations and agreements pertaining to the status of Palestine and other parts of the Arab world. All of the Palestinians’ efforts in this regard were either curtailed or blocked. Furthermore, early articulations on how the British should facilitate the Zionist project read almost identical to those that were included in the League of Nations Mandate granted to Britain over Palestine.

Settler colonialism was incubated by the British starting in 1917 and achieved success with the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. The British Occupation and Mandate should be designated as the actual date for this colonial project, which culminated in the dispossession and eventual expulsion of vast numbers of indigenous Palestinians. The Mandate provided the systematic infrastructure that led to the eventual establishment of a Jewish homeland while denying Palestine to the Palestinians.

The actual Mandate was adopted by the League of Nations on July 24, 1922, and came into effect on Sept. 29, 1923. As we approach the 100-year anniversary of WWI, the Sykes-Picot Agreement and the Balfour Declaration, it is imperative to re-center the discussion of Palestine around colonial discourses and place as much emphasis on British, European, and the major Western powers’ contribution to the dispossession of the Palestinians as we do on the Zionists in this regard. The time is right for London to publically admit that the Balfour Declaration was a major historical mistake, was illegal, led to ethnic cleansing and created a 12-million member Palestinian diaspora. Achieving peace is contingent on justice and can begin to take shape only when this original sin is admitted and recognized as such.